(CNN)In

his mid 40s, Mike Thomas went bald. Not a "little bald spot in the

back" kind of bald or "receding hairline" kind of bald, but almost

totally and completely bald. He was diagnosed with alopecia areata, an

autoimmune disease, and he was devastated.

He

looked, by his own description, like a "freak," with his eyebrows and

eyelashes completely gone. He could feel it when people looked at him.

Some of them quietly asked whether he had cancer.

"I'm

in the real estate business, and I'm active in my community, but I

started to shy away from people," said Thomas, who asked that his real

name not be used in order to protect his privacy.

"It affects every part of your life. I got very depressed, and it was horrible," he said.

Then, this year, Thomas took a little white pill used for arthritis, and within seven months, his hair grew back.

"It's incredible. I'm so happy to have it back," he said.

What this pill means for men with more common baldness

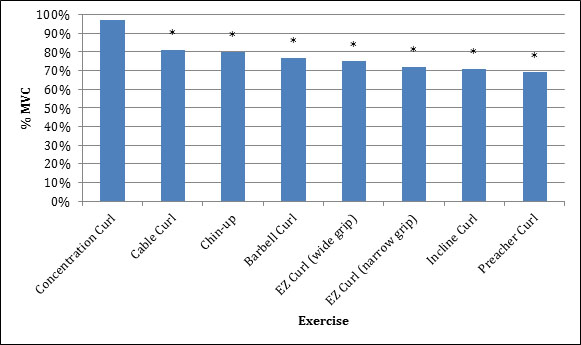

As part of a study

conducted at Stanford and Yale, Thomas and 65 other alopecia areata

patients took the pill, called Xeljanz, which is prescribed for people

with rheumatoid arthritis, another autoimmune disease.

More

than half of the study subjects saw hair regrowth. A third recovered

more than 50% of their lost hair. In a separate study, nine of 12

patients with alopecia areata recovered more than 50% of hair regrowth

using a similar drug, Jakafi, which is approved for cancer treatment.

Although

researchers say this is potentially great news for people with alopecia

areata like Thomas, what does it mean for men who have hair loss

because -- well, because they're men and they're older?

Thomas'

head may help answer that question. When his hair grew back, he still

had a receding hairline. That's because the Xeljanz pill gave him back

his 47-year-old head of hair, not his 25-year-old head of hair.

So

now Thomas' dermatologist, Dr. Brett King at Yale, is trying something

else: rubbing an ointment containing Xeljanz on the heads of men with

alopecia areata.

Will the men grow

back full heads of hair, or will they be like Thomas and many of the

other men in the study and grow back a head of hair with male pattern

baldness?

Dermatologists are deeply

divided between skepticism and optimism. King strongly suspects that

the ointment won't get rid of male pattern baldness. But others are more

optimistic.

Dr. Angela Christiano,

a co-author of the recently published study, had success with Xeljanz

when she made it into an ointment and rubbed it on the skin of mice with

skin engineered to be like the skin of bald men.

The ointment was rubbed on the right side of the mice and not on the left, and the results are plain to see.

Though

she thinks men might have the same success with an ointment, she said

the trick is that it has to penetrate properly. Compared with the

paper-thin skin of mice, human skin is "much thicker, and it's oily, and

it's deep, and it's got a fat layer -- so there's a lot to think about

when making a good topical formula," said Christiano, assistant

professor of molecular dermatology at Columbia University Medical

Center.

Why male pattern baldness is so hard to stop

Modern

medicine can treat big cancerous tumors and complicated neurological

diseases; it should be easy to get hair to grow, right?

"You

might think you could just sprinkle something on your head like what

you use to get grass to grow," said Dr. George Cotsarelis, a

dermatologist at the University of Pennsylvania.

But sadly, the physiology of hair growth is much more complicated than that.

King,

an assistant professor of dermatology at Yale, said that with an

autoimmune disease such as alopecia areata, you're essentially trying to

trick the environment surrounding the hair.

"It's

like making a plant in my house think it's springtime when it's

winter," he said. "You just throw a light up in the living room, and it

warms things up."

But with male

pattern baldness, you're dealing with a hair follicle that's pooped out.

"It's like taking a brown plant that's all but dead and bringing it

back to life again," he said.

And

much less money is spent on solving this problem than you might imagine.

"People think major pharmaceutical companies must be spending billions

of dollars on this because the payoff could be so huge, but that's not

the case," King said.

He

said big companies are concerned that the Food and Drug Administration

would approve a treatment for male pattern baldness only if it had no or

few side effects, since it's treating a cosmetic problem and not a

disease. Some men, however, say they suffer psychologically from losing

their hair, especially if it's at a young age.

Cotsarelis,

a professor at the Perelman School of Medicine, is working with

relatively small companies on stem cell therapies for male pattern

baldness and on tissue engineering, which involves growing

hair-producing skin on a tiny scaffolding and then transplanting it back

onto the scalp.

"In the end, I

think there are going to be multiple ways to treat male pattern

baldness, and some will work fabulously well in some people and not so

well in others," Cotsarelis said.